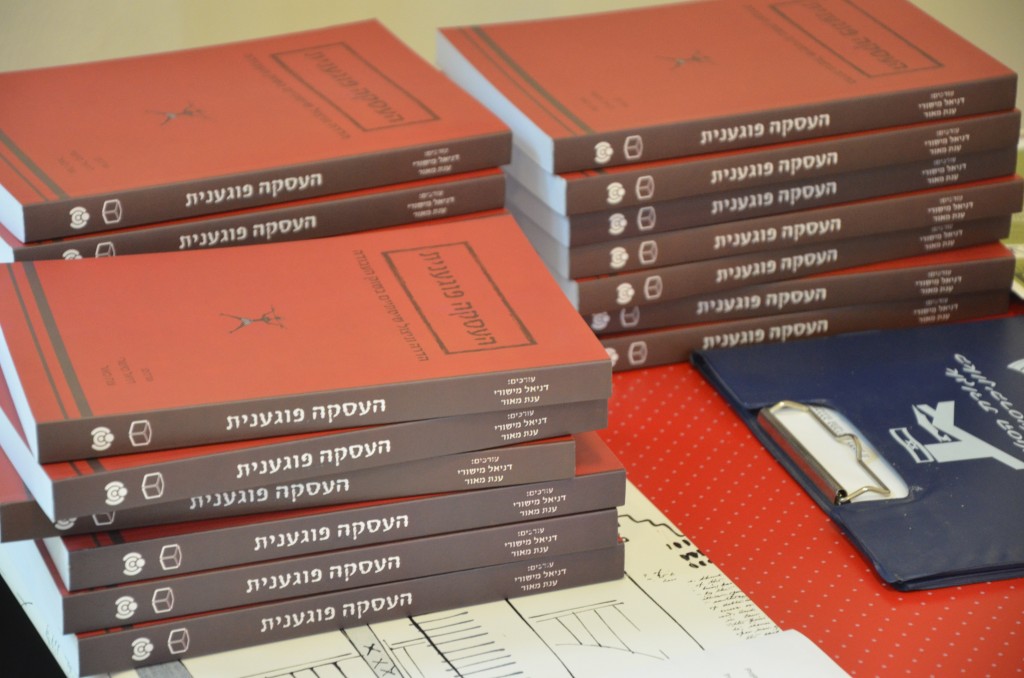

Precarious employment via employment agencies has reached the Israeli middle class. A collection of essays published by the Social Economic Academy offer cures for the malady.

Originally published in Haaretz, 12.8.2013

What do Sonol, the Open University, Pelephone, Cellcom, Clal Insurance, the credit card companies, Shefa Catering, Burgeranch, U-Bank, and a few dozen other companies in a variety of fields have in common? Their employees decided to organize with the Histadrut or with the smaller workers’ organizations, and form a union to represent them against the management. After years of fear and hesitation, many workers – in recent years their numbers have swollen to 60-70 thousand – decided to try and change the terms of their employment. It’s not class warfare, but it’s something.

These attempts at organization were influenced by a myriad of factors. The recession which started in 2008 and gave the employer the upper hand made many employees long for job stability. Protection against arbitrary terminations seems more important today than a pay raise. The increase in violations of workers’ rights, combined with the state’s feebleness in enforcing labor laws, also contributed to the will to organize. Another factor is the many forms of employment in Israel and the flourishing of a particularly precarious one: Contract work, or employment through go-betweens called “employment agencies,” or “service companies.” There are no exact numbers as to how many Israelis are employed by these companies, but estimates place the number at 300-400 thousand, or over 10 percent of salaried employees – well above the average in developed countries.

Therefore, “Precarious Employment: Systematic Exclusion and Exploitation in the Labor Market” is relevant today, and probably will be for many years to come. Precarious employment patterns were not created yesterday, but developed in Israel over decades. Those most exposed to them are immigrants, minorities, migrant workers and, in recent years, a growing portion of middle class Israeli-born citizens. Outsourced employees in general and those employed through agencies in particular are everywhere: In both the public and the private sectors, in retail and in the manufacturing sector, in local municipalities and in government offices. Even the education system, including higher education, has been infected. Precarious employment occurs when the direct or indirect employer deliberately attempts to keep pay or benefits from the employee. It is an attempt to discriminate between employees under a legal guise, or by a flagrant violation of the law, in denial of the employer-employee relationship obligations.

The book’s editors, Dr. Daniel Mishori and Dr. Anat Maor, as well as most of the writers represented in it, have backed workers’ struggles against precarious employment and for workers’ right to organize. The book draws on many examples of exploitation in universities (perhaps because most of the writers are academics themselves), and less on cases of exploitation in factories, municipalities and private businesses.

The first part of the book generally outlines precarious or discriminative employment and links it to privatization. Economist Itzik Saporta claims that in Israel, the administration and the employers both consider what happens in the workplace to be of no importance. The dominant discourse, not only among employers but among the general public as well, is not about terms of employment but about markets, supply and demand, and interests. This discourse paints a picture in which the market allots every employee with what he deserves relative to his contribution to his employer’s profits.

Prof. Itzhak Harpaz claims in his essay that the Israeli job market at the start of the 21st century is reminiscent of the 19th in terms of discrimination and harassment of different sectors of workers, expressed by violation of labor laws and collective agreements. Dr. Efraim Davidi writes that workers were always grouped into opposite types in Israel: First, Israeli workers versus Palestinians, which were later replaced by migrant workers – the principle always being getting cheap labor. Davidi claims the government encourages precarious employment patterns. Anat Maor says that since the 80s, especially between 1997 and 2007, Israeli governments led processes of dismantling organized labor and lowering labor costs, ignoring their duty to defend disenfranchised workers.

Prof. Dani Gutwein links between precarious employment and privatization, which aims at dismantling organized labor in Israel. “Privatization is a political project which serves the interests of capital and is responsible for the dismantlement of the welfare state,” Gutwein writes. “Thereby the middle class’ social security is eroded, while the lower classes are pushed below the poverty line and gaps between different sectors increase.” Prof. Gadi Algazi and Orly Benjamin warn that these processes of privatization and discrimination are currently at work in universities, mostly damaging non-tenure track lecturers and the administrative and custodial staff.

Attorney Itay Svirski, one of the founders of Koach La Ovdim – Democratic Workers’ Organization in 2007, reaches the conclusion that given the lax enforcement of employment norms by the state and by the Histadrut, organized labor and unions are the most effective tool to realize workers’ rights. The writers testify that the pessimism they felt while writing the book has given way to more optimistic feelings, which may be due to a positive trend in 2012, following a new pro-workers legislation package and the 2011 protest movement. It would have been better if the book was not authored only by academics and professional unionizers, but also by politicians and public figures from across the political spectrum, including members of government. Then, the book could have influenced circles outside those which are already aware of the magnitude of the problem of exploiting disenfranchised workers and leaving them out to dry.